Encrypting Secret Messages in Music: Mercury, or, the Secret and Swift Messenger

Taken by the author. This copy of John Wilkins’ Mercury; or, the Secret and Swift Messenger (2nd ed., London, R. Baldwin 1694) is held in Yale University’s Beinecke Library. Call number: X117 641wb

Imagine that you are a musician in a royal European court in the 1600s–but you’re also a secret agent for a different government’s intelligence services. (Several musicians at this time were, in fact, international spies; John Dowland is a famous example.) How will you transmit sensitive information to your contacts without getting caught? Perhaps you could hide your message in a musical composition! No one would ever suspect you–after all, playing music is your job. Now, all you need is a musical cipher: a system for turning text into music.

John Wilkins sketches out just such a system in Mercury; or, the Secret and Swift Messenger. Wilkins was neither a musician nor a spy, but in 1641 he wrote this book about secret communication (reprinted 1694). Mercury was the messenger of the Roman gods, and he was also associated with hidden, even magical knowledge. In Mercury, Wilkins explains how to encrypt messages using numbers, letters, or other symbols, including music notation.

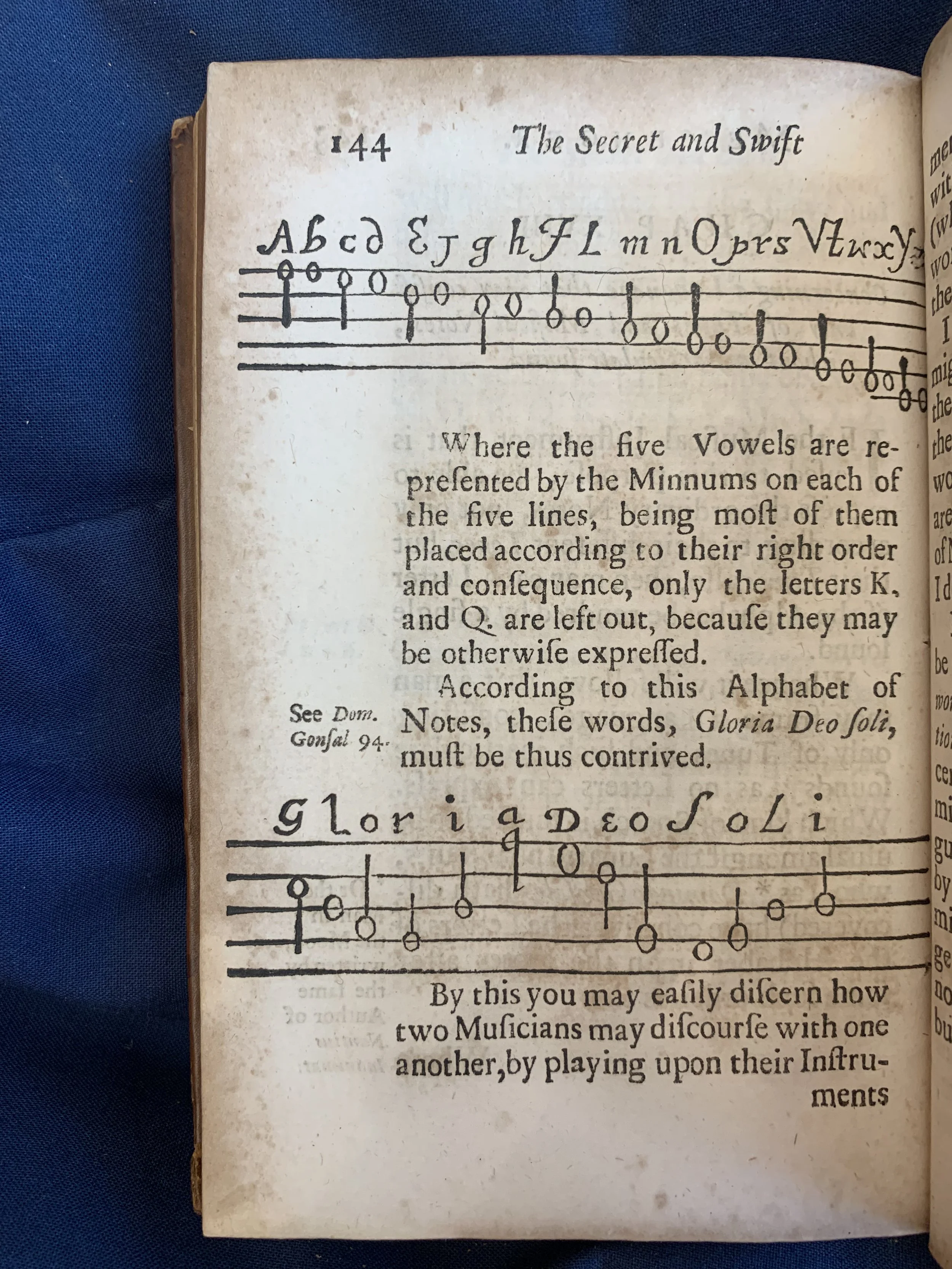

Wilkins’ cipher substitutes a different note for each letter of the alphabet. However, there are only 7 notes in a diatonic scale–not enough to cover the whole alphabet. Wilkins gets around this problem in two ways. First, he assigns different letters to different pitch registers. As you can see in the picture, the letters A and S are represented by the same note, but the A sounds an octave higher than the S. Second, Wilkins attaches different rhythmic values to different letters. For example, A and B are represented by the same note in the same octave, but A is shorter than B. (The musician must decide which clef to use, and which pitches to assign to a few letters that Wilkins skipped).

Spying was not the only reason to be interested in musical ciphers. In the 1600s, many scholars were studying how meaning could be transmitted using symbols and scripts. Some thought that if they could unlock all secrets of human communication, it would help them to understand the mathematical “language” of the universe. Back then, music was categorized as a branch of mathematics, so musical symbols seemed like a logical way of connecting language and numbers. Several musical ciphers survive from the seventeenth century, and the most widespread was probably the one in Athanasius Kircher’s Musurgia Universalis (1650). Kircher was more interested in mysterious languages and symbolic scripts than in espionage. Still, his cipher is similar to Wilkins’: they both use a range of pitches to represent letters of the alphabet.

So, how effective is a musical cipher? Give it a try using this digital interface (courtesy of the University of Michigan). You can input your own message into Wilkins’ cipher, listen to the encryption, and download an audio file to share with a friend. What do you think? If you were a spy, is this how you would transmit secret information to your contacts? We don't know for sure whether Wilkins' cipher was ever used by real-life musical spies, but you might be the first. One thing is certain: if the point of cryptography is to confuse readers, musical ciphers certainly do the trick!