Inside Handel’s Beehive: If Classical Pieces were Animals

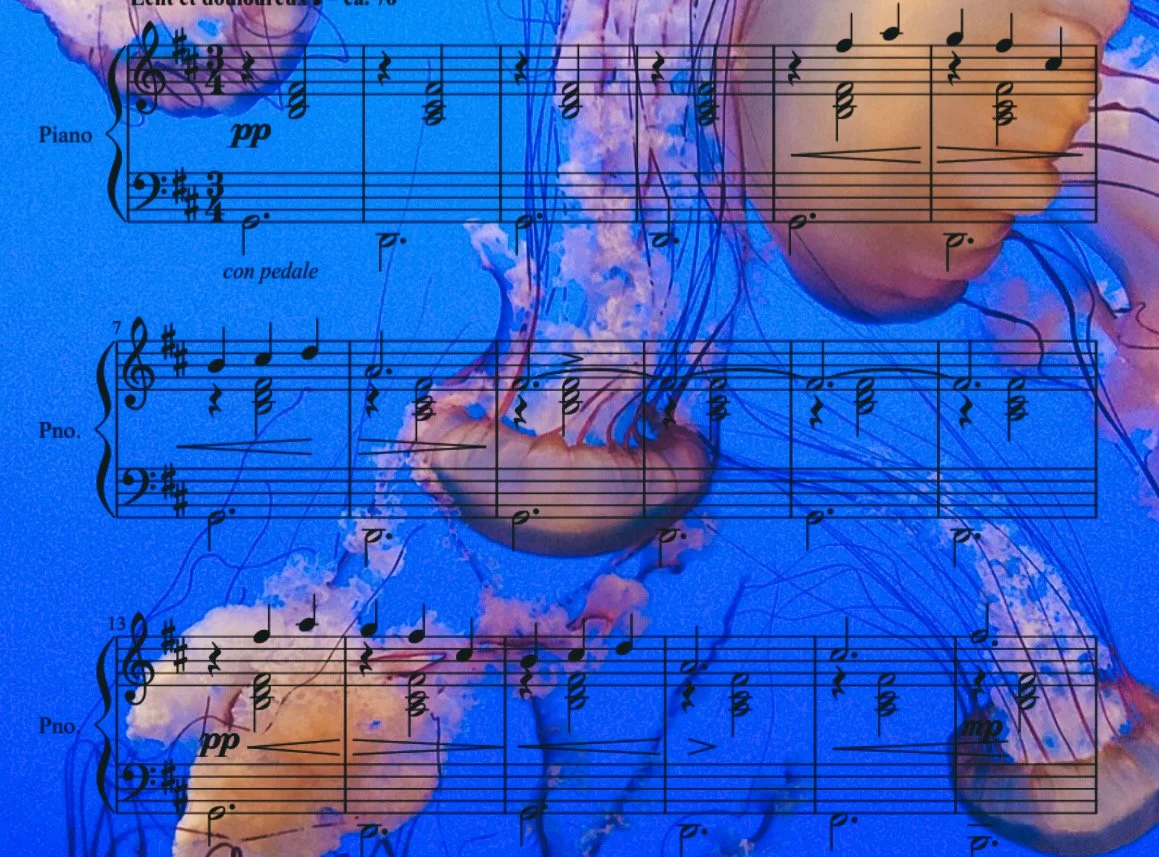

Collage by Isabel May. Photo of jellyfish by Photollama, Wikimedia Commons

Although many people find themselves put off by the grandeur of classical music, it has more to offer for the imagination than we may think; looking at the big classics through new lenses can make them far more interesting than black and white notes on a page. In advance of Earth Day this Monday, imagining well-known classical pieces as animals offers new ways of bringing music to life!

Ludwig van Beethoven: Moonlight Sonata (1st movement)

It’s easy to fall asleep to Beethoven’s Moonlight sonata- and in a good way! Its consistent triads take us on a slow-moving journey through different chords, moods, and ideas whilst remaining inside a cozy pattern not drifting too far from a still night-time scene. As we settle into this comforting idea, a delicate melody flying above it all tells us what our animal is; a bright-eyed, wide-winged owl. This animal balancing on a smooth melodic thread has the age and wisdom to hold us by the hand on a journey feeling both stable and changing. Listening to the less familiar movements of the sonata may help us discover which other animals make up the nocturnal scene.

George Frideric Handel: Messiah; Hallelujah

If someone sang the first "Hallelujah" motif, it's probably one of few classical melodies many people would be able to continue. Its jumpy, memorable intervals, heavy, confident chords, and ascending key changes create one of the Church's most fiery pieces. It isn't difficult to imagine the bustling members of a loud church choir as buzzing bees fighting for movement and power in their nest. The piece is bright, colourful, and lively (if perhaps sometimes a little too loud…)

Eric Satie: Gymnopédie No.1

This piece’s distinctively widespread melody and gentle chordal texture means it’s often one of the first pieces new pianists take up. The low but warming bass note/chord pattern builds a swaying foundation whilst the higher melody jumps about above. Different recordings often choose different speeds, but almost always have a sense of freedom as they move. This reliant but irregular pulse recalls the tentacle waves pushing a jellyfish along, with its higher jumpy line more like the bright electrical shapes we see in its head.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Fugue in D minor

Ok, hear me out; a curly-wig seventeenth-century man may not bring to mind this unusual, lively animal; but listening to the style more intently may make you think differently. With the vibrant, plucked strings of seventeenth-century keyboards (harpsichords) being unable to create the decadent sustained chords of Satie and Beethoven, each melodic line in these pieces is sharp, bouncy, and characterful. The “fugal” compositional style also means we eventually hear four individual melodic lines interacting, yet with their own character and keyboard territory. Picturing each as a hopping meerkat looking at the others before it chooses what fascinating area to hop to next doesn't seem too far off to me; and makes each line far more interesting to follow.

So, from mushy French melodies to a lively, buzzing Messiah extract, these animal visions of classical works offer a new way into finding their character, even if not in the way their composers may have expected.

Subscribe to our free electronic newsletter or follow us on Instagram @teenworldarts

You might also enjoy:

Sumina Studer, Violinist and Music Entrepreneur: London’s Hidden Music and Art Spots

Tiffany Poon, Pianist: A Rising Star on Her New Album “Diaries: Schumann”

Six Favourite Dance Movies in NYC (Unranked)

Eating the Opera: The Recipes Behind Three of Italy’s Most Celebrated Composers