What is the Music of the Spheres?

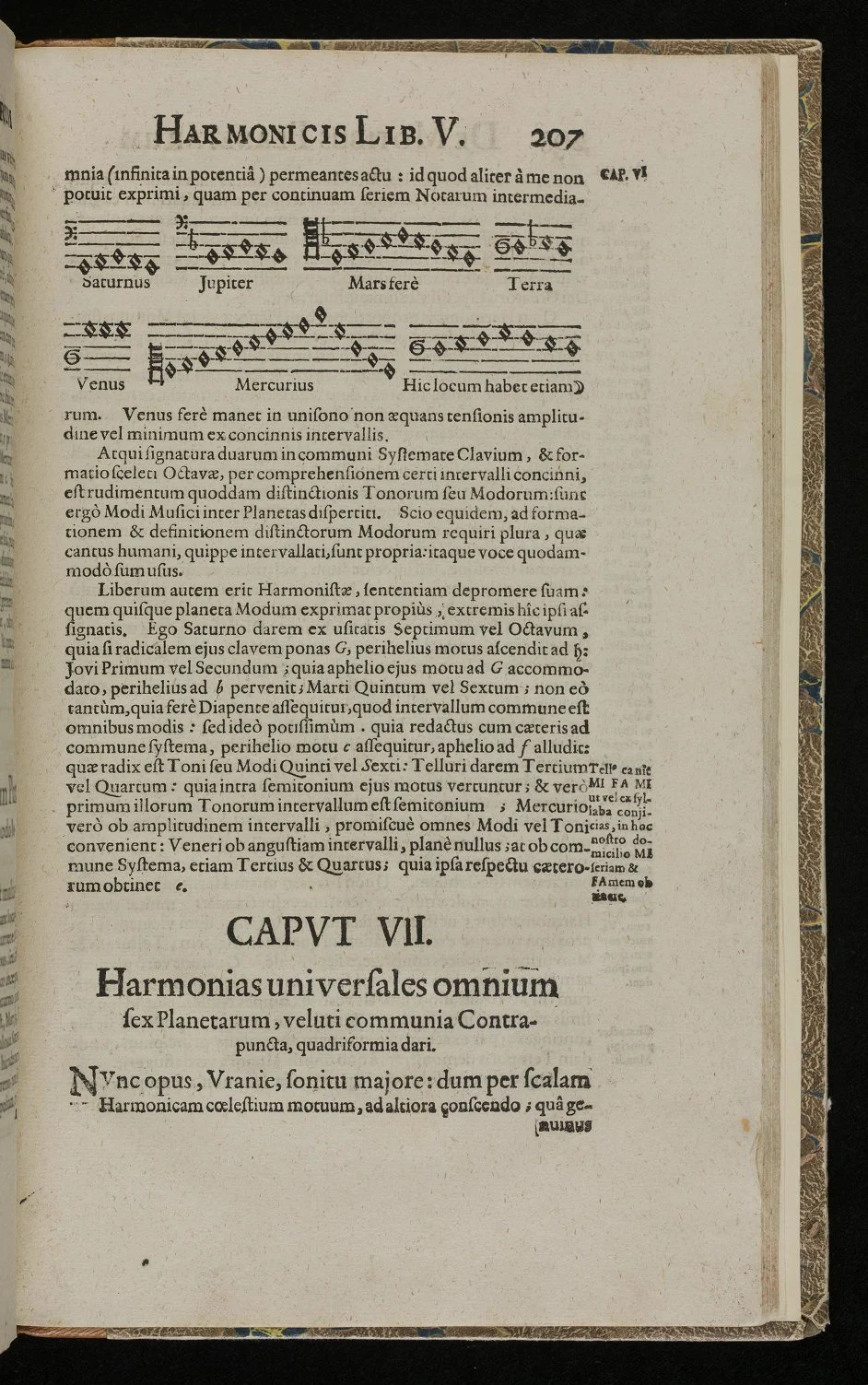

Scan of the first edition of Johannes Keppler’s Harmonices Mundi (Harmony of the World). The page contains the musical scales that Kepler attributed to the six known planets of the time, and the moon, which described their orbital motion.

J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Silmarillion (the backstory to The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings) opens with a creation myth in which a divine council forms the cosmos by singing it into existence. Mortals cannot hear this music, but it is still part of everything they are, since their whole universe consists of celestial harmony and dissonance turned into matter. Tolkien’s evocative fantasy story is actually based on ancient ideas from our own world. Both Eastern and Western philosophers wrote about music’s power, but Tolkien was probably most familiar with scholars like Plato, Aristotle and Boethius (a Roman who died c. 525). In one way or another, these thinkers all described the structural patterns of space-time itself as a kind of inaudible music. The analogy goes like this: music theorists look for relationships and patterns of movement between sounds; likewise, physicists and astronomers are interested in relationships and patterns of movement between objects in nature. Boethius, drawing from his ancient Greek sources, described three levels of cosmic music, but only one is audible:

- Musica mundana or musica universalis, often referred to as “the music of the spheres,” is the coordinated movement of natural elements, especially planets and stars. Throughout history many people have believed that the movements of heavenly bodies affect everything that happens on earth (horoscopes are today’s version of this belief), so the music of the spheres shapes human history as well as the cosmos—this also happens in The Silmarillion.

- Humans consist of lots of different parts (physical, emotional, and spiritual). Musica humana is the inner harmony of a human being, echoing the music of the spheres.

- Finally, musica instrumentalis is what we usually think of as “music:” sound which is organized in ways that humans hear and enjoy.

Today, we usually describe the material world using more scientific terms. But just like science, music theory involves a lot of math. Anyone studying rhythm, scale degrees, chords, etc. will have to use numbers, ratios, and proportions. This is why most pre-modern thinkers thought of music as mathematics in motion. They understood audible harmony as a sonic model of the marvelous, intricate way that everything in the cosmos works together.

Throughout the ages, the music of the spheres inspired scientists as well as artists and writers. In 1619, the astronomer Johannes Kepler used musical notation to create “diagrams” of planetary motion in his book Harmonices Mundi. Kepler argued that the proportions of musical harmonies are similar to the proportions between planets orbiting the sun. His astronomical theories were an important contribution to the Scientific Revolution, even if his numbers were a bit inaccurate. In our own time, Nobel prize-winning physicist Frank Wilczek writes about mathematical beauty in the relationships of subatomic particles (A Beautiful Question, 2015). Wilczek, too, affirms the ancient insight that everything in space-time is structured according to harmonious mathematical patterns. The music of the spheres is such a compelling idea that it continues to be updated, revised, and re-imagined even today!