Happy Birthday, Igor Stravinsky! Celebrating an Icon of Twentieth Century Music and Ballet

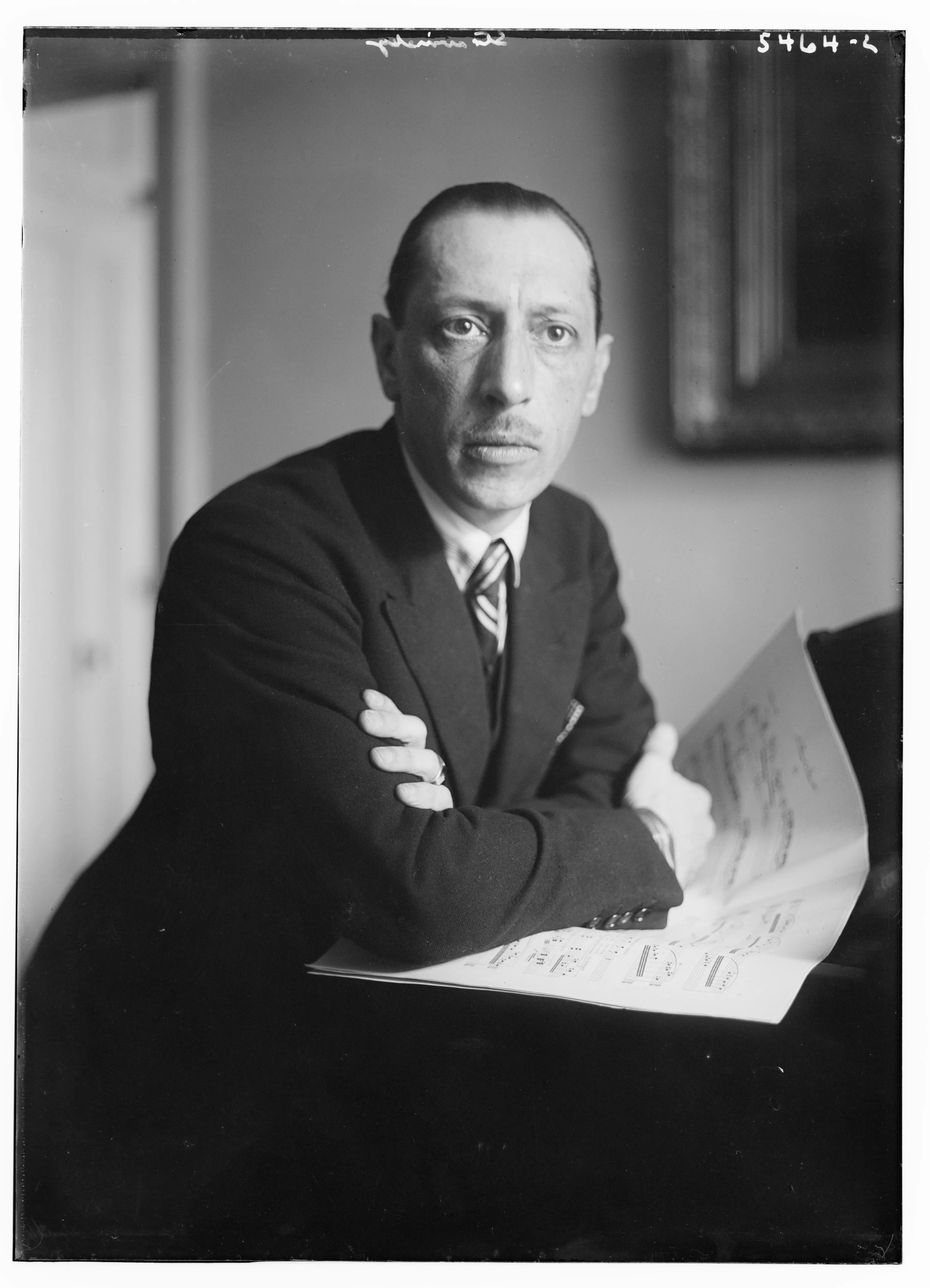

Igor Stravinsky. Wikimedia Commons.

There are few ground-breaking composers who are also famous for their ballet compositions. If Pyotr Tchaikovsky and Sergei Prokofiev are the only ones who come to your mind, think again: Igor Stravinsky is one of the most important composers of the twentieth century and an icon of modernism, but his most famous compositions were created not for the concert hall, but for the ballet.

Late Start

Stravinsky’s path in music was unusual. Many famous composers discover their special gift for music early in life, but not Stravinsky. Stravinsky was born in Oranienbaum outside of St. Petersburg on 5 June (17 June, New Style) 1882 into a musical and literary family. His father was a leading opera singer, and little Igor received lessons in piano and music theory. But nobody noticed any unusual musical talent in the boy. Stravinsky went on to study law and philosophy at St. Petersburg University. He only discovered his love for composition as a student. At age twenty, he showed some of his pieces to the father of a fellow law student: the influential composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, a member of the group of composers known as The Mighty Five, who established a distinct national, Russian style of classical music. Rimsky-Korsakov took on Stravinsky as a private student, tutoring him chiefly in his own specialty, orchestration.

The Firebird

In 1909, Stravinsky attracted the attention of the impresario Serge Diaghilev. Diaghilev had just started to bring seasons of Russian ballet and opera to Paris, an enterprise that soon developed into the legendary company of the Ballets Russes. Diaghilev’s concept was revolutionary: his vision was to bring brilliant, short original ballets to the stage that put just as much weight on the quality of the music and the design as on the choreography and the dancers. Over the years, he would bring together pioneering composers, choreographers, dancers and artists to create sensational works that were the talk of the town. Diaghilev first commissioned Stravinsky with some orchestral arrangements, but then asked him to compose his first ballet combining various Russian fairy tales for his 1910 ballet season in Paris. The result was The Firebird. Stravinsky’s magical and intense music provided the perfect vehicle for Mikhail Fokine’s expressive choreography, interacting with Leon Bakst’s imaginative and exotic costumes and Alexander Golovin’s stunning sets to create a masterpiece. The young, unknown composer became famous overnight. One year later, Stravinsky composed another major success for Diaghilev’s company: Petrushka, a one act ballet set on a Russian fairground.

The Rite of Spring

Stravinsky’s third ballet for Diaghilev led to one of the biggest opening night scandals in music history. It also turned the composer into an icon of modernism. At the turn of the twentieth century, all art forms underwent radical change as artists began to search for different artistic languages. In painting, this led to the first abstract paintings. In music, composers challenged the standard way of organising harmonies, melodies and rhythm. On 29 May 1913, The Rite of Spring (Le Sacre du printemps) shocked its Parisian audience at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées with its dissonances and daring irregular rhythms. The music created an atmosphere of brutal primitivism that perfectly suited the ballet’s subject, a pagan ritual culminating in the sacrifice of a virgin maiden to spring. The choreography created by star dancer Vaclav Nijinsky shocked the audience just as much as the music. Instead of admiring ballerinas on pointe, they were looking at turned-in dancers in foot cloths stomping their feet and contorting their bodies into heavy, angular shapes. From the moment the curtain went up, laughter and shouts pitted those who opposed the work against those who loudly defended it, making it almost impossible for the dancers to focus on the complex music. Even though the work was performed only seven times, it became a symbol of modernism.

Apollon musagète (Apollo)

One year later, World War I broke out. Stravinsky and his family were stranded in Europe, spending most of the war in Switzerland. The composer’s success in Western Europe had already uprooted him from his homeland. After the Russian October Revolution in 1917, his separation from Russia became permanent. Stravinsky settled in France. The exile also entered a new phase in his music. Gone were the days of melodic references to his homeland. His style became more restrained and entered a neoclassical period: Stravinsky would take his inspiration from a composer or musical style from Europe’s classical music past, and offer his own, innovative interpretation focusing on order, balance, economy and clarity.

In 1926, maybe out of guilt because he was having a passionate long-term affair while neglecting his wife, or maybe because events in Soviet Russia depressed him, Stravinsky had a religious reawakening. He also started to be influenced by the philosopher Jacques Maritain, who opposed the romantic idea of the artist as an inspired genius creating masterworks, promoting instead the idea of the artist as a craftsman who makes honest, simple creations. In 1927, Stravinsky began to work on Apollon musagète (today known as Apollo), another one-act ballet for Diaghilev. Apollon musagète showed the birth of the god Apollo and his education through the three muses Calliope (poetry), Polyhymnia (mime) and Terpsichore (dance).

The ballet became a defining moment for another young Russian émigré, the twenty-four-year-old choreographer George Balanchine: “Apollo I look back on as the turning point of my life. In its discipline and restraint, in its sustained openness of tone and feeling, the score was a revelation. It seemed to tell me that I could dare not to use everything, that I, too, could eliminate.” The ballet is now considered the first neoclassical ballet, the defining choreographic style of twentieth century ballet. Neoclassical ballet is rooted in the classical tradition of the Russian imperial ballet but strips it completely of its narrative content and flamboyant theatrical sets and costumes. What remains is the dance itself, telling its own story in a modern, stream-lined way. Over the decades, Balanchine revised Apollo several times, getting rid of sets, costumes and much of the story. It remains a signature work of Balanchine’s company New York City Ballet, and the oldest Balanchine ballet in the company’s repertoire.

Agon

Balanchine’s and Stravinsky’s collaboration reached its peak with New York City Ballet’s 1957 premiere of Agon. After spending many years in France, Stravinsky had moved to the United States in 1940, settling in Hollywood in California. At the time of his work on Agon, Stravinsky was emerging from a creative crisis: after World War II, the master of modernism suddenly felt that he was no longer relevant. The musical avant-garde had turned away from neoclassicism towards the serial, or 12-tone compositional techniques of composers such as Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg and Anton Webern. Instead of using a traditional scale as basis for a composition, 12-tone technique works with the twelve tones of a chromatic scale (the twelve semitones, or half-steps of any octave; put simply: imagine sitting in front of the piano and playing twelve white and black keys in sequence). The result: atonal music that is not based on a specific, traditional key signature.

In Agon, the old master found his answer to the young avantgarde’s experiments: Agon is Stravinsky’s version of a serial composition, but also continues neoclassicism’s flirtation with the past because the score’s pieces were inspired by a 17th-century French dance manual. The complex score was brilliantly expressed in Balanchine’s boundary-pushing choreography that still looks utterly contemporary today, almost seventy years after its premiere. The original cast of the central pas de deux also challenged racial standards of mid-twentieth century America: it was performed by Arthur Mitchell, the first black dancer to reach the level of principal in an American ballet company, and Diana Adams, a white principal dancer.

Conversing animatedly in their mother-tongue, the exiled composer and choreographer shaped the course of twentieth century music and ballet. Balanchine choreographed around forty works to Stravinsky’s music. In 1972, one year after the composer’s death, Balanchine paid homage to his comrade-in-arms with New York City Ballet’s Stravinsky Festival: thirty ballets to Stravinsky’s music were performed in one week, twenty of them new, created by seven choreographers. In 2022, New York City Ballet celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the festival with another two-week celebration of Stravinsky’s music. Stravinsky’s legacy therefore lives on in two art forms: classical music and ballet.