Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Just Went Live: TwoSet Violin and the Magic of Livestreamed Classical Performances

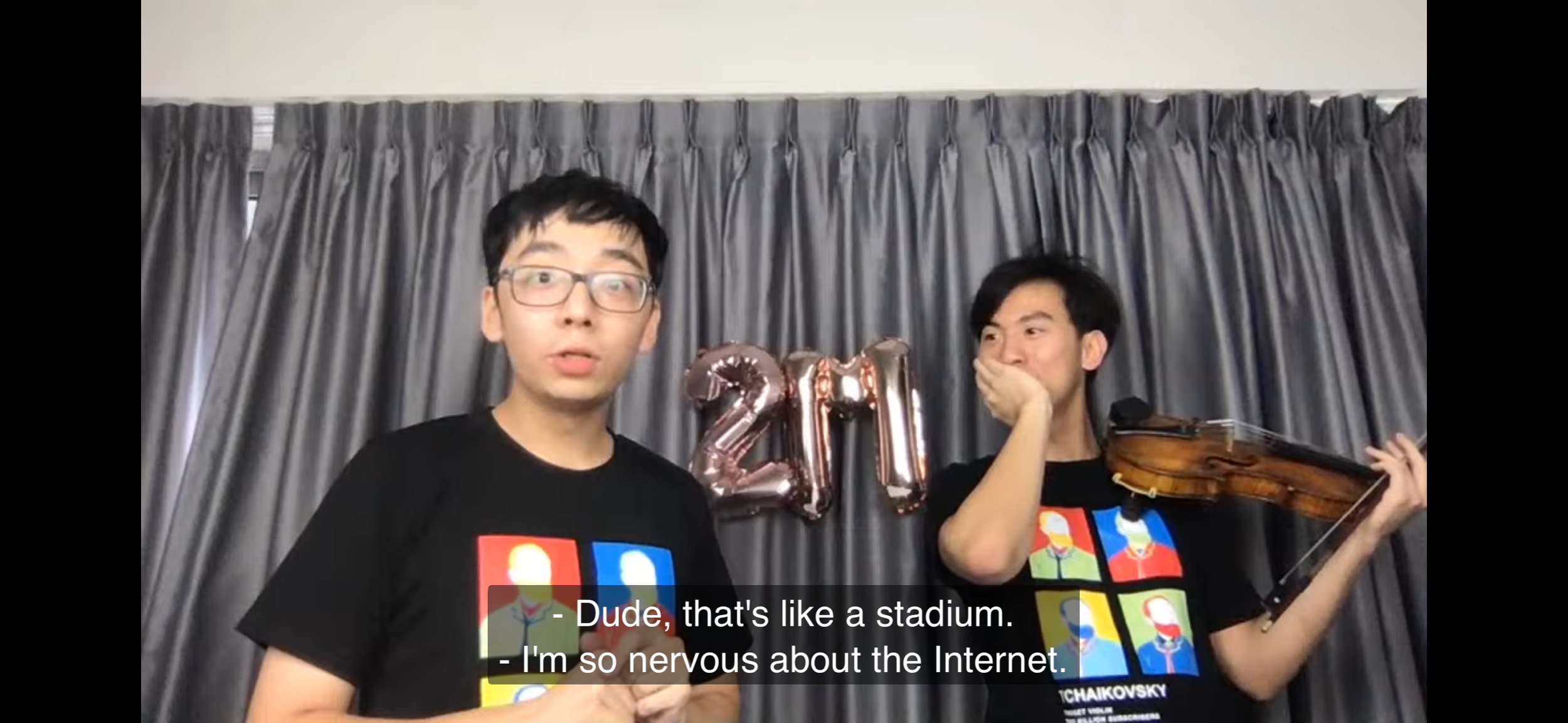

A performance of Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto in D major. Soloist: tick. Live audience: tick. Orchestra: None to be found. Concert venue: a nondescript room somewhere in Australia. In it are two musicians, a camera, microphone, and an admirable degree of ambition. The performance in question is, of course, Brett Yang and Eddy Chen’s livestreamed celebration of reaching two million subscribers on their popular YouTube channel, TwoSet Violin. To say the livestream bears little resemblance to a standard concert performance of the concerto is perhaps an understatement. The pair wear graphic tees; Chen plays a rough orchestral reduction on his violin. The near-50,000 strong live audience is of a scale unimaginable in traditional venues and is dispersed around the globe. Throughout the performance a constant stream of messages floods the chat feed. In many ways this is a new look for live classical performance, with an international virtual audience chattering away whilst the musicians play. And yet, curiously, such involved listening arguably harkens back to a bygone historical period when audiences used to clap and clamour and accolade musicians, before concert practices settled into the respectful silence of today’s classical performance culture.

I love this livestream video and its sequel, in which Chen performs Jean Sibelius’ violin concerto to commemorate 3 million subscribers. There is something special about the festive atmosphere of celebration, the pair’s relatable nervousness, and the slightly make-shift set up, combined with their evident skill as musicians. They capture the pure joy and exhilaration of this music and the act of performing it, a feeling often lost in the perfectionist professionalism of traditional classical performance. The two performances are thoroughly enjoyable watches which I recommend to anyone who hasn’t seen them. They are also fascinating and surprisingly complex examples of the cultures of social media and classical performance interacting.

Though the livestreams are a far cry from concert-hall performances, the musicians do aim to maintain some recognisable aspects of standard concert practice. Most fundamentally, these are serious performances of concert repertoire to a live audience. The evocation of standard concert practice is further enhanced by a moment of delineation between the stream’s preamble and its musical performance. Proceedings begin with Brett and Eddy casually welcoming incoming viewers, sorting technical issues and such. When ready, Brett exclaims that they ought to “walk onstage”, prompting the two to amble out and then back into frame. This is partially a joke about a YouTube livestream pretending to be a physical concert – there obviously is no stage. But it also prompts a genuine conceptual shift, with the two swapping their chirpy YouTuber personas for the more serious demeanours of musicians preparing for a demanding performance. In that moment, the proverbial houselights dim and the performance begins properly.

Just as the two performers are creating the atmosphere of a standard classical concert, the virtual audience also plays their part. Though not physically present to be seen or heard by the musicians, they can communicate via the live chat function, and thus in written and emoji form applaud when one might in a concert and whoop at the end of the performance. A more amusing way in which these audiences evoke the behavioural norms of a classical audience is the sporadic comments of ‘*cough*’ throughout the performance and in between movements. This again riffs on the comedy of a virtual audience playing the part of a physically present one and references previous TwoSet videos laughing at the tendency for audiences at classical concerts to cough up a lung in between movements.

There are also, unsurprisingly, many ways in which these livestreams are dissimilar to traditional performances. The practical considerations are obvious: the loss of audio quality and acoustic, the orchestral accompaniment being in reduction, the mediation of a digital platform like YouTube. More interesting is how the live chat allows audiences not only to jokingly simulate standard concert etiquette but also move beyond it. Being able to comment during the performance itself without causing audible disturbance to the musicians allows for a constant stream of feedback. Audiences aren’t limited to showing appreciation at the end of the piece, as in person, but do so after every movement, after extended virtuosic passages, or even particularly enjoyable phrases. In other words, this feature of the digital platform allows for a far more responsive and interactive mode of audience behaviour. Interestingly, you can also see both performers looking at the chat when they have rests and being buoyed by the positive feedback. With this, the performances truly become a two-way communication to an extent that is absent in today’s traditional concerts.

Such absence was not always the case, though. There is an interesting correlation between the audience behaviour during these livestreams and historical conventions that existed before the habits of decorous silence that we still have today developed. Sources from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries indicate that noisy audiences, expressing both satisfaction and disgruntlement, were the norm. Passages were applauded, movements repeated. One only has to read the colourful memoirs of Hector Berlioz for a sense of the rather carnivalesque atmosphere that was prone to develop in the Parisian opera houses (I highly recommend looking up the “Claque” for an amusing historical oddity in this vein). Contemporary performers talk about sensing if an audience is on their side or not, but historical musicians hardly required such quasi-telekinetic discernment to tell if their efforts were being appreciated or not. This behaviour ultimately waned across the 19th century for a multitude of reasons, but particularly as a Romantic aesthetic disposition developed that prioritised a profound, internal, and fundamentally individualised experience of music.

I don’t see today’s classical audiences reverting to their ancestors’ noisier habits any time soon (though with the breakout success of performers like Anna Lapwood drawing heavily from pop performance practices, I might come to eat my words). However, what the TwoSet Violin livestreams show are a glimpse of the more communal and responsive listening experiences of times past. It’s a great irony that these virtual performances, with an audience spread disparately around the world, have a greater sense of collective engagement than those in which everyone is sat in the same room. In person performance is and always will be the heart and soul of any musical culture. Nonetheless, these videos make a great case for another kind of classical performance in which audiences are invited to see a more personable side of the performers and react in real time alongside their fellow listeners, rather than be isolated in their own experience of the music.

TwoSet’s livestreamed performance Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto

…and their subsequent Sibelius violin concerto livestream

Full 4 Million Subscriber concert with Singapore Symphony Orchestra