A Murderous Artist Pardoned by the Pope: Benvenuto Cellini and the Art of Punishment

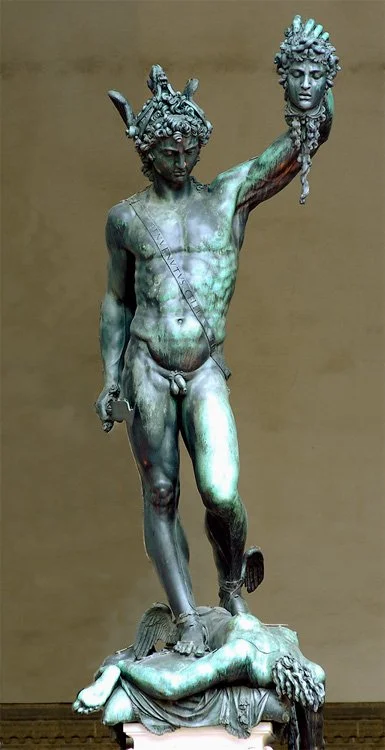

Benvenuto Cellini, Perseus with the Head of Medusa, 1545-1554, bronze

In the twenty-first century, violence and murder are strictly monitored by our legal system, striving to ensure order and safety. The system seeks to identify murderers and criminals quickly and to try them fairly. But during the Italian Renaissance, the enforcement of the legal system looked quite different. In some notable cases, such as the murders by Benvenuto Cellini, Renaissance artists were able to escape punishment unscathed due to their fame and success. On the other hand, artists were sometimes called upon to carry out criminal punishments using publicly displayed Pittura infamante (defamatory paintings), which worked by tarnishing the criminal’s honor and reputation.

One of Italy’s most criminal yet skilled artists was Benvenuto Cellini, an award-winning goldsmith and sculptor lauded by Pope Clement VII. But he was also vengeful and violent, supposedly decapitating the man who killed his brother and stabbing his rival goldsmith Pompeo de Capitaneis to death. This leads us to wonder, can we catch a glimpse into his double-life as a criminal through his art?

In the mid-sixteenth century, Cosimo I de’ Medici commissioned the bronze sculpture Perseus with the Head of Medusa for the Loggia de Lanzi in Florence. As Perseus stands over Medusa's decapitated body, he is presented to the viewer as a supposed hero. Yet, unlike other renditions of the mythological tale, Perseus averts ours and Medusa’s gaze as he is unable to confront the brutality of his actions. Some believe that this aversion unveils not only Perseus’ remorse but also Cellini’s, given his murderous history.

Not all, but some Italian Renaissance artists held a higher social status. As evident in Cellini’s detailed sculpture, the ability to create an original artwork directly from the artist’s imagination requires immense talent. Because of this, artistic creation was commonly linked to God’s creation—which further elevated the status of skilled artists. What could this mean for celebrated artists who committed a crime? After fleeing to Naples, Cellini was pardoned for his murders by Pope Paul III and his cardinals. His honour remained intact and stronger than ever in certain circles. Interestingly, Cellini wrote an autobiography documenting some of his kills and illustrating his taste for violence.

But Renaissance artists were not only criminals—they also played a role in serving justice. Since many privileged criminals, such as Cellini, would flee to avoid punishment, an alternative arose: artists were commissioned to create Pittura infamante, which have been likened to the modern day wanted poster. These images depicted criminals shamefully, humiliating them and damaging their reputations. Pittura clearly identified the criminals and were publicly displayed on the sides of buildings, such as the Bargello.

Pittura infamante were designed to stand in the place of a real punishment in the absence of the criminal, and as such mimicked the punishment for each particular crime. For example, Andrea del Sarto’s preparatory drawing displays a criminal hanging upside down held by one foot, which would have been the punishment for treason. Since these paintings were hung outside and regularly rotated, historians today reference the preparatory drawings that still survive. The public display caused such shame that the painting could have been considered an actual punishment. The crafting of these artworks was thus like administering a severe physical punishment. Therefore, artists had an immense distaste for these commissions, some taking them begrudgingly in secret while others flat out refused. Unlike today, honour was crucial to the Renaissance man. And even more central was art— allotting a very different role to artists in the cycle of crime and punishment.

Andrea del Sarto (b. 1486-1530), Preparatory sketches for a pittura infamante

You might also enjoy. . .