Ballet Across the Globe: George Balanchine

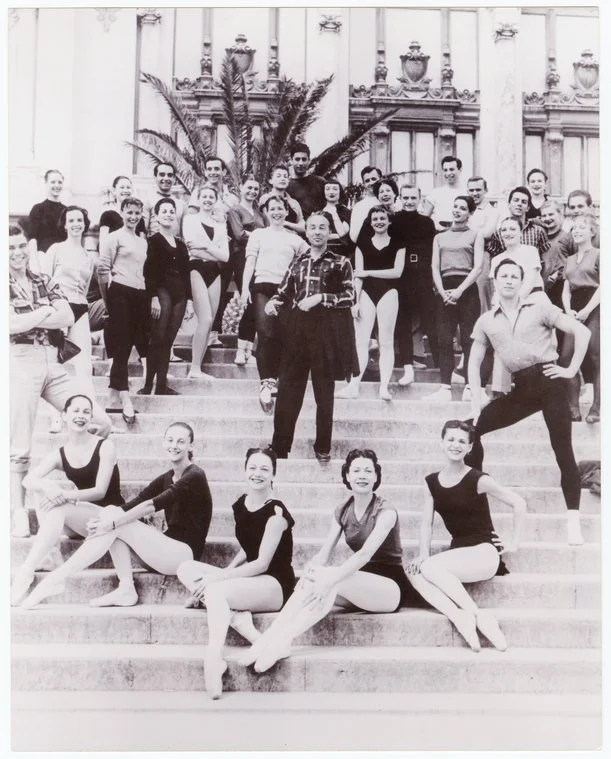

George Balanchine, 1942. Photo by Joseph Janney Steinmetz

Among ballet’s founding fathers lies one such man who many revere and even consider responsible for the birth of ballet in America: George Balanchine. Balanchine’s choreographic style, referred to as neoclassical, demonstrates his fluency with classical ballet and his knack for melding it with modern stylistic sensibilities. Over his lifetime, he choreographed a total of 465 ballets spanning from more minimal works such as Agon and The Four Temperaments to the full-length story ballet A Midsummer Night’s Dream. His legacy has lived on, not only through his ballet school, The School of American Ballet (established in 1934) and his company, New York City Ballet (established in 1948), but through the timeless nature of his work that blends his love of movement and music .

Georgi Melitonovich Balanchivadze was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, on 22 January 1904 to Georgian opera singer and composer Meliton Balanchivadze and his second wife, Maria Nikolayevna Vasilyeva. He studied piano at five and began ballet training at the Imperial Ballet School in St. Petersburg at the age of nine. At sixteen, he choreographed his first ballet titled La Nuit and graduated at age seventeen, joining the Mariinsky Theatre, where he danced until 1924. After graduating, he continued to study music for three more years at the Petrograd Conservatory where he learned piano, music theory, composition, harmony, and counterpoint. In 1922, he organized a small experimental troupe called Young Ballet; the company was granted permission to leave Soviet Russia and tour. It was on this tour that the troupe chose not to return to the Soviet Union and settled in Paris. Soon after, Balanchine was invited by Serge Diaghilev and joined the Ballets Russes as a choreographer at twenty-one. He created Apollo and The Prodigal Son for this famed company and collaborated with composers and artists such as Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Prokofiev, Erik Satie, Maurice Ravel, Pablo Picasso, and Henri Matisse. After Diaghilev’s death in 1929, Balanchine choreographed for various companies in Paris, London, Copenhagen, and Monte Carlo until 1933, when Lincoln Kirstein invited him to America to establish a ballet school and company after seeing his work with Balanchine’s new experimental company, Les Ballets. After coming to America and founding The School of American Ballet in 1934, Balanchine and Kirstein set out to create a company: American Ballet. The company became the Metropolitan Opera’s resident ballet company, but after a few years of dissatisfaction between them, the company and the Met parted ways in 1938. Balanchine began to work on theater and films. In 1941, Kirstein and Balanchine established another company called American Ballet Caravan. The new company toured South America with ballets like Concerto Barocco and Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2. By 1946, the company was renamed Ballet Society, and finally, in 1948, the famed name New York City Ballet was adopted.

Over the next 35 years, Balanchine drastically redefined ballet, shunning plotlines and moving into abstraction and athleticism. Highly musical, he saw dance as a visualization of music, hence his iconic saying: “See the music, hear the dance.” His choreography necessitates extremity, whether through deep plies or quick petite allegro - intricacy and detailed musicality lie at its core. NYCB Principal dancer Maria Kowroski tells us in this short snippet of Agon that, “I feel in this Pas de Deux, we are having little moments of daring one another throughout.” - a throughline that can be found in many of Balanchine’s works. Here, Gelsey Kirkland dances in Theme and Variations, her attention to the downbeats in the solo are especially clear and Balanchine’s capacity to highlight every section of the music shines as we watch her embody the beat. This notion of fearlessness, courage, and limitless devotion to his vision, no matter how demanding, makes Balanchine’s work distinctive and revolutionary. He said to his dancers, “Why are you stingy with yourselves? Why are you holding back? What are you saving for – for another time? There are not other times. There is only now. Right now.” Neoclassicism was born at a time that had revered tradition, and spearheaded an alternative means of balletic expression through energetic, dynamic approaches to movement.

George Balanchine surrounded by his dancers from the New York City Ballet, 1955