From London with Love: On Lee Miller and the End of Innocence

My dearest artlings,

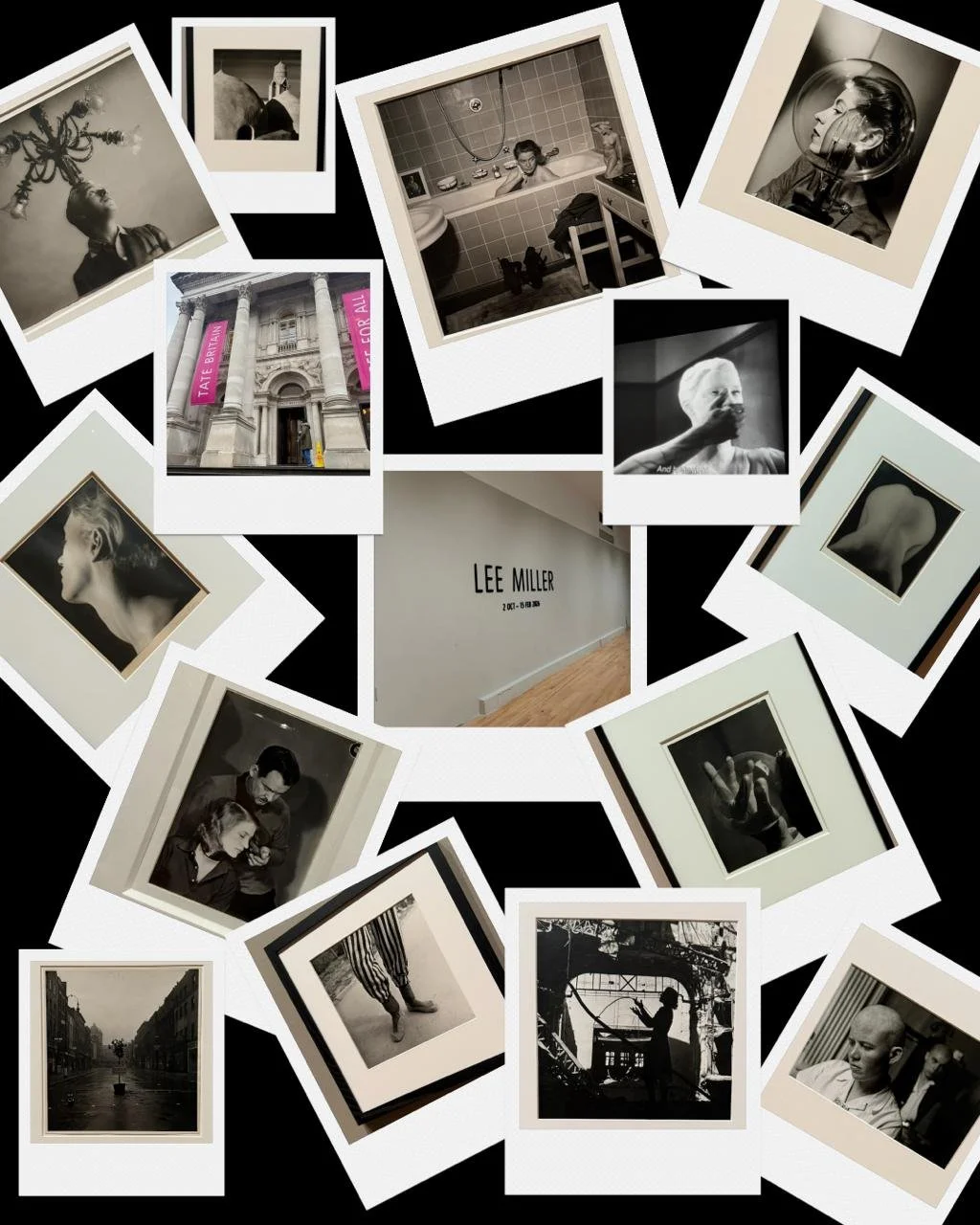

I thought it would be fun. What could be so serious about a beautiful blonde model becoming a photographer? This time, the joke was on me. I climbed the stairs on a Wednesday afternoon, as rain slipped into the Thames and drifted past Millbank behind my back. Two posters guarded the entrance: Tate Britain on the left, Free for All on the right. Then, inside, another: Lee Miller, Floor One. That’s where I was headed.

Walking in, I stopped Before the Camera, to encounter Lee Miller’s beginnings: her father’s photography, and her own modelling. What a beautiful woman, I thought. So did Man Ray. When Miller arrived in Paris, she presented herself to the time’s leading photographer unannounced. “I will be your student,” she said. But she became more than that. A lover and collaborator, she helped him probe the erotics of photography. The product of that–images of love, power, and desire–stand scattered throughout Dreaming of Eros, capturing Lee’s delicate neck, tilted back, begging to be kissed; her nude torso, a reminder of the primacy of matter over thought; and her collared throat, as Man Ray looms above, dominating. The aftermath is clear, too: her body pressed against the mattress; bubble pipes in bed; and sleep–hers, then his.

That same intimacy permeates the next rooms, shaping her visions of cities and countries. A Surreal Gaze documents her experience of Paris, with its passageways, inflamed condoms, and perfumeries. New Visions reveals Cairo, Syria, Turkey, and Romania, depicting their Bird Rocks, ancient ruins, and round white domes with a clarity that left no qualms about photography’s claim to art.

Passing through the next halls, I briefly meet her Artists and Friends–Charlie Chaplin, Picasso–and pass by her Vogue days, which we both find rather frivolous. But if depth is what she sought, she certainly found it during the war. Britain at War opens with Charlotte Street, mere minutes from where I live. Emptied of its cafés and lunch spots, it stands as she saw it: hollowed, bombed, Blitz-torn. I’m suddenly inside a London I have, thankfully, never known. Censored pictures complete the story: the Burlington Arcade, reduced to rubble, and the roof of UCL, shattered. Neither depicts enough undamaged material, as per the Ministry of Information’s guidelines.

Then come the burns, hospitals, and casualties, all testimonies to violence. Overwhelmed by In the Field, I move too quickly into the next room, only to realise–too late–what it contains. Buchenwald. Dachau. Piles of starved bodies, and a dead man’s eerie smile, piercing right into me. I face captured guards, SS men floating in canals, and dead deportees sprawled beside railway tracks. Miller even climbed into a train with the dead to photograph decomposing bodies. Death is everywhere, echoing her plea: “I implore you to believe this is true.” And huffs, so many huffs, of everyone watching.

I was not prepared for this room; I expected to stay in the land of Vogue, of Eros. But I was at war–and then, amid its wreckage, so was she. It’s no wonder she never recovered. A picture hints at why: photographed in Hitler’s tub, Lee sponges her neck, paralleling the Venus sculpture to her right. A pair of boots rests on the bathmat, implicating the belongings confiscated and lives lost. Hitler’s portrait on the left personifies the cause–and its consequence, the millions of prisoners murdered in gas chambers disguised as shower rooms. That, I feel, is the most startling picture of the show—it humanises monstrosity. Miller’s domination of Hitler’s private apartment, requisitioned by US forces shortly before she arrived in Munich, and the intimacy of his bathroom, collapses the distance between here and there, now and then, posing a reminder to our inherent capacity for evil. People are whispering: this can happen again, an older lady turns to her husband. This room’s quieter than the previous ones, and the unease is palpable. She talks of Greenland and Iran, of protests and killings. I register the words, but they do not quite reach me.

The aftermath is all-consuming: women with shaved heads, reunited families, thin to the bone, and bullet-splintered glasses. Ladies sit among destruction, and the Vienna opera house lingers in ruins, reminding me of the city that survived on eight-hundred calories a day–and music.

A picture speaks a thousand words. And Lee Miller spoke sixty thousand of them.

With a heavy heart,

Maya