Holy Cow! A Semi-Skimmed History of Milk in Visual Culture

Alonso Cano, Saint Bernard and the Virgin, c.1645-52, Museo del Prado

Milk might seem like an ordinary item on the weekly grocery list, but over the course of ten thousand years, the legendary white liquid has been twisted into a rich and everchanging cultural symbol. To begin with, the ancient Greeks believed the universe itself was but a splatter of spilt milk from the breast of the queen of the gods - hence “The Milky Way.” This creationist myth associated breast milk with a religious level of nourishment, its mystical life-giving qualities finding its way into Catholic paintings of nursing madonnas, where the Virgin Mary breastfeeds her son or even St. Bernard,thirsty for holy wisdom.

Hera suckling the baby Heracles at her breast, surrounded by Aphrodite and Eros (not visible here), Athena (on the left), Iris (on the right) and a woman, perhaps Alkmene (not visible here). Detail from an Apulian red-figure squat lekythos, ca. 360-350 BC. From Anzi. British Museum

These spiritual elevations of milk began its long-standing association with purity and whiteness. However, when cow milk was commercialised, an opposing world of meaning was met. Though the robust, practical milkmaids of Vermeer and other Dutch artists appear to romanticise a wholesome pastoral life, this sort of domestic virtue made them subjects of male voyeuristic desire. Cartoons, nursery rhymes, and literature made these figures at first romantically suggestive but stereotypes soon developed into more lewd ideas. Surrounded by attractive vanitas, like jugs and produce, milkmaids became not just amorous, pretty figures, but ones of secretive adultery. Their milk too, from the Dutch slang “melen” meaning “to sexually attract or lure,” perhaps originating from men watching farm girls under cows, became connected to these not so wholesome encounters. In English towns,milkmaids traditionally dressed up and danced in front of their customers to sell their dairy products. This is not the only time that sellers of milk have been sexualised. The profession of milkmen has also been connected to sexual promiscuousness in television and film - usually as they would visit the home when the husband was away at work - an opportune time for adulterous activity.

Johannes Vermeer, The Milkmaid (c. 1658–1661). Oil on canvas, 45.5 x 41 cm (17.9 x 16.1 in). Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

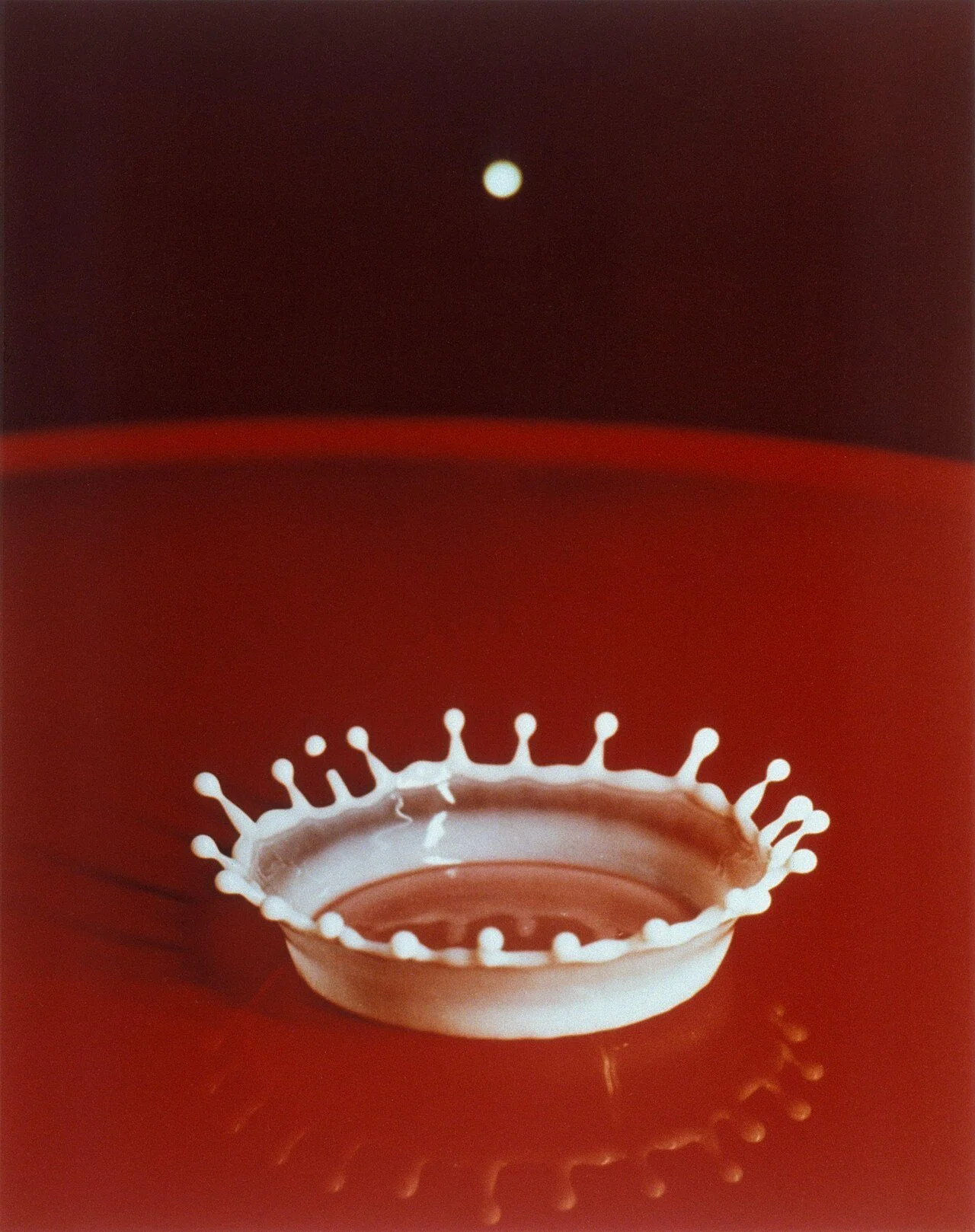

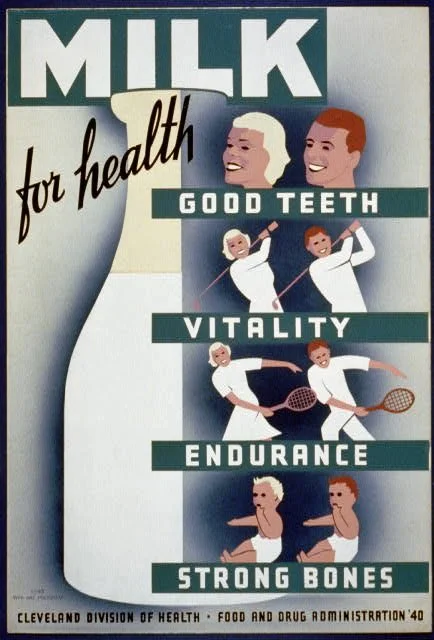

The mythos around milk's visuals returned to an elegant beauty at MOMA’s first photo exhibition, seen in Edgerton’s 1936 photograph, Milk Drop Coronet. Picked for its high contrast and opacity, milk advertisers took inspiration and used such visuals to increase their sales, which after WW1 and a fall in overseas trade, required immense boosting. US president Ronald Reagan launched several advertisement campaigns which glorified milk and its made up biological benefits due to the government's billions of dollars of surplus milk. Not only was milk connected to strength, bone health, and weight-loss, but advertisers put a patriotic spin on this marketing. Milk became a liquid that could be connected to white, nuclear families, and a kind of social purity. These racial supremacist and nationalist ideas are perhaps why controversial politicians and figures have been attacked with milkshakes on several occasions.

Milk Drop Coronet, Harold Edgerton, 1957 and WPA Milk Poster, 1940.

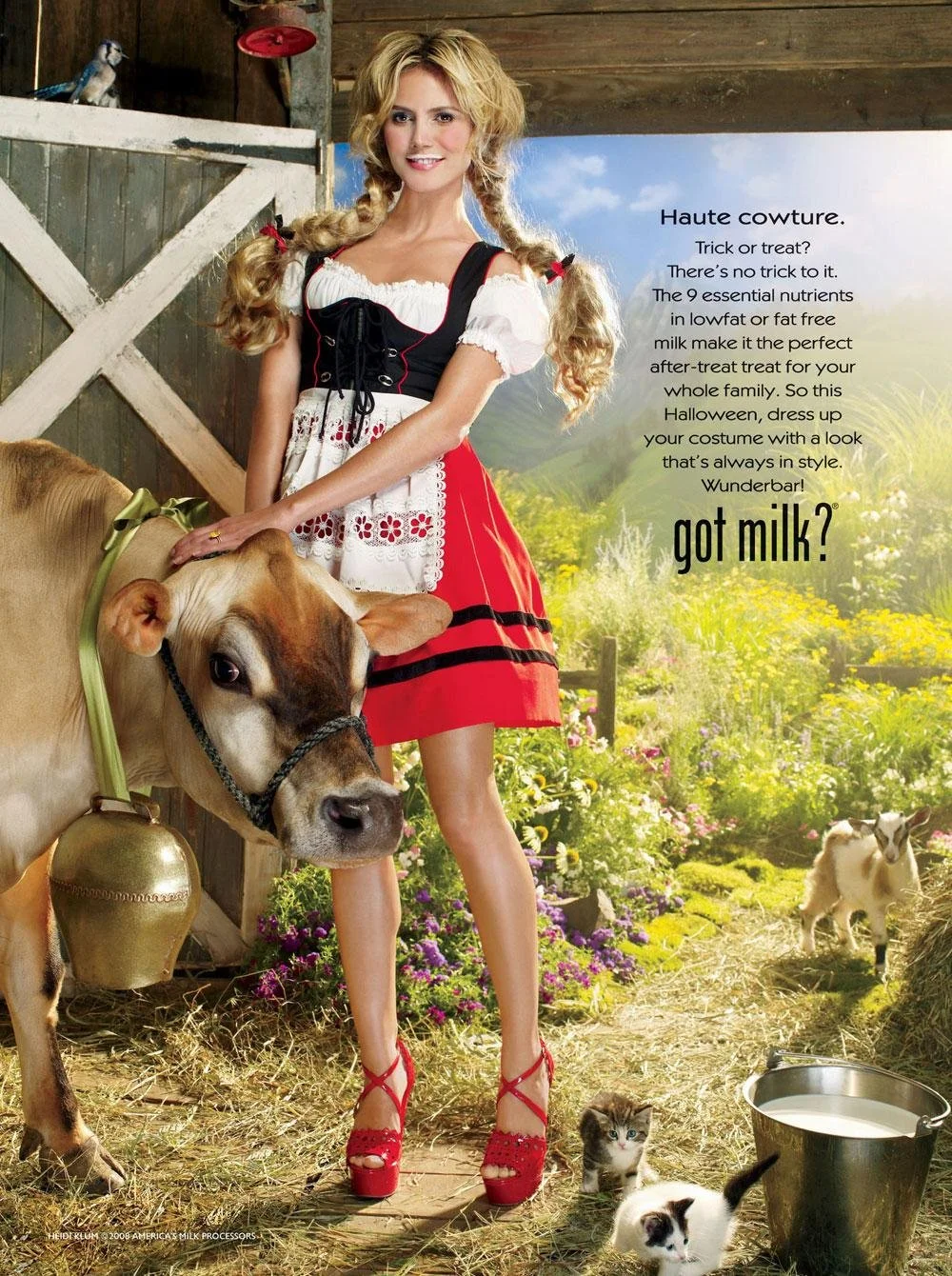

What in every other mammal is a drink purely for infants, was impressed as an important miracle beverage of vitality for children as milk advertising in the US expanded into mandatory drinking at school lunches. The infamous “Got milk?” campaign in the 1990s and 2000s featured comedic television adverts and celebrity endorsement which transformed milk into a mainstream treat, popular with American stars, and also captioned as the reason for their success, beauty, and strength. A wide number of actors and athletes were chosen, but also a selection of scantily dressed supermodels, who were sometimes even costumed as milkmaids, repeating the traditional image of centuries ago, commercialising the tasteless gag into a marketing strategy.

Heidi Klum “Got Milk?” Poster, 2008. Image published for educational purposes only.

This long history of endorsement in advertising and characterisation of purity and goodness has inevitably been experimented within art and cinema. Think Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange, where milk is spiked with drugs, and comes to represent the opposite of its preconceived innocent childishness, or its allusions to racism in the films Inglorious Bastards or Get Out.

Milk has clearly charged our collective imaginations as watchers and makers of its visual appropriation. Humans have warped it into not one symbolic socio-political entity but a completely contradictory plethora of symbols between histories and fictions where it stars as an uncanny drink that fulfills whatever need it is conjoined to -- be it supernatural and genetically enriching, or exploitative and darkly sinister.

Still from A Clockwork Orange, Stanley Kubrick, 1971. Image published for educational purposes only.