Who Do You Dance For? Looking Into Degas’s Dancers and Ballet Itself

Edgar Degas, The Rehearsal, 1874, oil on canvas. The Burrell Collection, Glasgow

It’s easy to write off Edgar Degas’ ballerinas as monstrous–and the artist himself as a misogynist. With descriptions like raw, uncouth, and animalistic clothing his dancers, and social historians dubbing nineteenth-century ballet a mere means of survival and social elevation for poor, young girls, the narrative surrounding Degas’ visions of the ballet has become quite biased. Worse, it has neglected one simple truth: that ballet is, above all, a form of art. Luckily, a closer look into Degas’ dance scenes reveals he, too, was aware of that–and used painting to elevate both ballerinas and their craft.

A bit of backstory: by the 1850s, ballet occupied an uneasy position in France. While the Romantic era had established the ballerina as an ethereal, otherworldly ideal, as crystallised in La Sylphide, the industrial era ruptured the fantasy. At the newly built Paris Opéra, ballet was both a prestigious public spectacle and a precarious profession, sustained by the labour, aspiration, and vulnerability of working-class girls. Their motivations were socially questioned, with many saying that these girls danced not to express an art but to find patronage from wealthy men.

Degas, of course, knew this. Unlike his contemporaries, however, he recognised dancers not as social climbers or companions, but as artists whose art required discipline, talent, and preparation. Nowhere is this more obvious than in The Rehearsal, one of his earliest engagements with ballet (see image above). Constructed from sketches, memory, and imagination, the painting renders young dancers in a newly built Hausmannian studio, practicing under the watchful gaze of their instructor. In the background, a troupe of dancers perform an adagio; and, in the foreground, a mother assists her daughter with her costume as another girl waits by their side. This emphasis on preparation, in itself, distances ballet from the popular notion it was a mere means of escaping poverty or attracting patronage. Instead, it highlights the endless preparation–steps, routines, costumes–at the heart of its practice. The staircase cutting through the composition adds a witty layer to this reading: partially obscuring a dancer’s body, its curved ascent echoes the arc of a pirouette, while its steps evoke the literal vocabulary of instruction drilled into dancers. And even if it nods to social climbing, it nonetheless underscores the complex nature of ballet, preventing trivialising arguments.

Edgar Degas, The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage, 1874, oil on canvas. The Met, New York

Degas’ choice of material was also important. Towards the end of his life, and largely due to his deteriorating eyesight, he turned to pastel–the medium wrongly associated with his “coarse” or “animalistic” depictions of women. Posing a contrast to the highly refined polish of oil paint, which shows ballerinas smoothly executing practiced movements, as in The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage, pastel reinforced the worked, corrective, tactile sensations of practising ballet off-stage. Subtly, it asserted the experiential reality of learning and witnessing dance, posing a sharp contrast to both ballet’s romantic idealisation and cynical reduction.

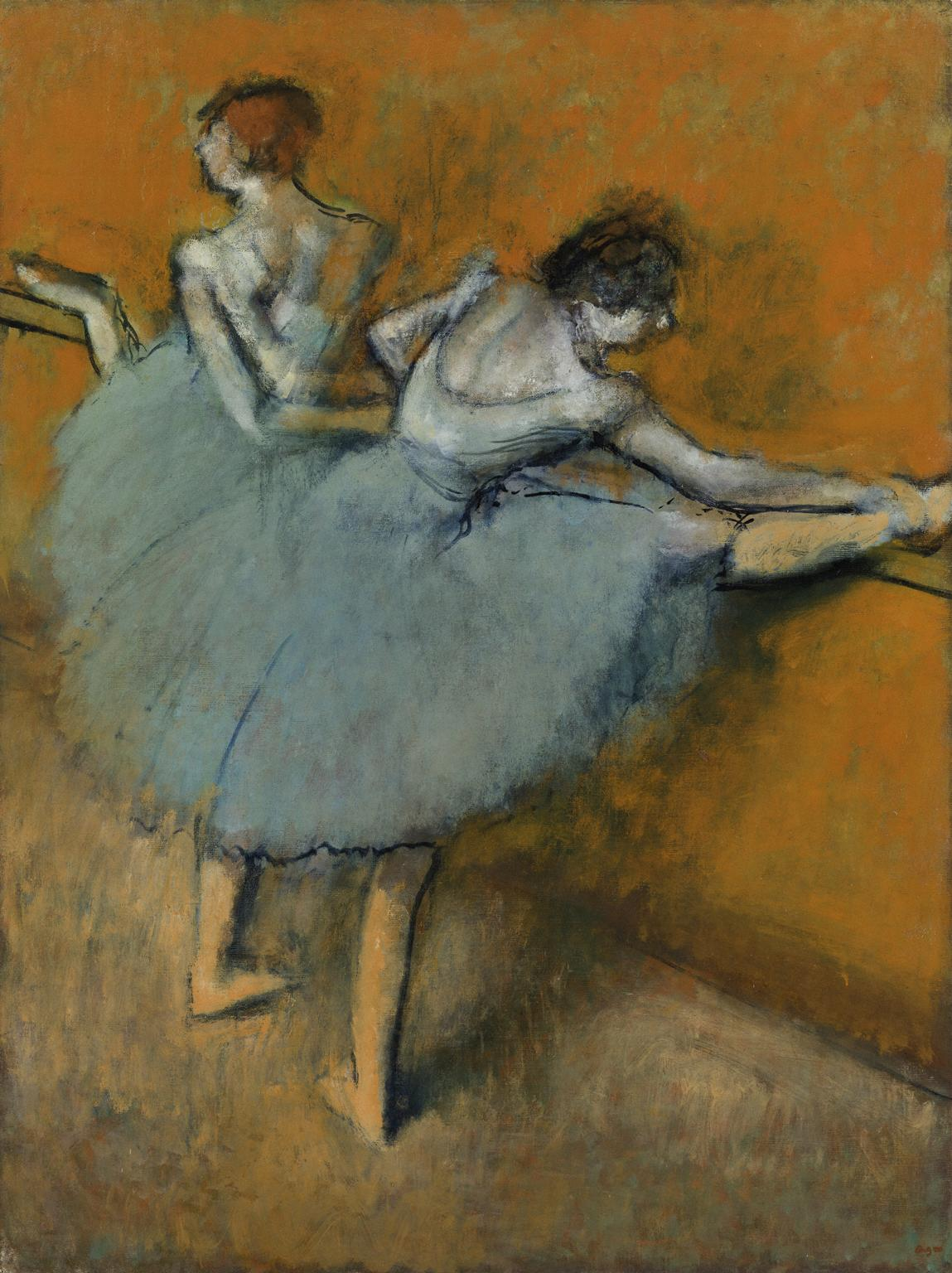

Edgar Degas, Dancers at the Barre, c. 1900, mixed media and pastel on paper. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C

To do so, works like A Group of Dancers and Dancers at the Barre (see image above) present ballerinas in their more private moments, huddled in a group discussion after class or hunched over a barre to practice their movements. These girls are not aware of the viewer’s gaze; and none is performing to be seen. They are practicing their art form, dedicated to improvement and mastery, a pursuit then solely reserved for male painters and musicians. And the medium of pastel itself, demanding continual tactile handling–pressed, dragged, corrected, and reworked–mirrors the process of preparation, in which the dancer’s body is repeatedly shaped through instruction and touch. This creates a compelling dichotomy, aligning dancer with medium and instructor with artist. As the implied yet unseen instructor and artist shape, adjust, and correct, both medium and dancer submit to a process of disciplined formation, reaching cohesion through sustained handling and control. Pastel, then, does not denigrate Degas’ dancers; it foregrounds their labour, reasserting ballet as a disciplined practice grounded in physical effort, tactile correction, and artistic mastery.

In that case, the following becomes obvious: despite objections to the contrary, Edgar Degas saw ballet not as a superficial ploy for social flourishing or an ethereal fantasy that could be enacted without effort; but as a rigorous, disciplined practice–an art form that took a toll on dancer, instructor, and artist, uniting them in a continuous movement towards mastery.